Shuffle Your Library: The Book History of Magic: The Gathering

[This post is a slightly expanded transcript of a talk presented at the 3 November 2021 “Books On Screen” Symposium]

My name is Allie Alvis. I’m a book historian, rare book cataloguer, and I’m one of the estimated 40 million players of Magic the Gathering, the fantasy tabletop card game. Although it features many fantastic settings, the world of Magic does not exist in a vacuum; it draws from a bevvy of real-world objects and media to create worlds that feel both new and, at the same time, accessibly familiar.

One item that features heavily in the lore, mechanics, and aesthetics of Magic is the book. Books permeate the many worlds of Magic in both a physical and functional sense. Cursed tomes, libraries, and book-devouring monsters are common features of card art and accompanying stories. And on a meta level, the cards themselves are meant to represent books. Magic’s relationship with books and their physical forms comes from a combination of the creators’ innate conceptual knowledge of books and direct referencing of specific objects. Numerous writers, artists, and developers collaborate to create and release a new set of cards every quarter. These sets are generally conceptually related, but take place across numerous very different settings. But even in particularly alien realms, we often find a codex or a scroll. Now able to be played in digital form as Magic Arena, the game has added a variety of animated assets that bring even more dimension to the cards. I have interviewed several artists associated with Magic the Gathering and its parent company, Wizards of the Coast, in order to get a sense of where the inspiration for the books, scrolls, libraries, archives, and other bibliographic card features come from. Their references range from the broad idea of the book to their personal collections, to on-site library visits, as well as a healthy dose of general internet image scouring. By examining the bibliographic aspects of the gameplay and art of Magic through a material culture lens, we can form an image of how physical bibliographic concepts are translated into the game. We can also get a sense of where the artist find their reference material, and what that might mean for libraries.

The bibliographic specifics of Magic will be clearer with a basic understanding of the setting of the game, and its mechanics in general. Magic the Gathering, which I will also refer to as simply Magic, was created by American mathematician Richard Garfield and is published by games company Wizards of the Coast. The first set of Magic cards was released in August 1993. The basic concept of the gameplay of Magic is that the players are Planeswalkers -- magical beings that can move between different planes of reality -- and they are engaging in a wizardly duel by casting spells and summoning creatures. The cards represent these creatures and spells, as well as the magical energy needed to cast them. To win, a player must get their opponent’s life total to zero by attacking them with creatures and spells.

Each creature and spell has a different energy cost referred to in-game as mana. There are five colors of mana, each generated by a specific kind of card called land. You can see the types and their associated magical ideologies in the color wheel adjacent. A player needs different colors of mana to cast different creatures and spells, and builds their deck around a single color or, more commonly, around a combination of two or more colors. Cards that feature books tend to require blue mana for casting, blue being the color of intellect, knowledge and learning.

In Magic terminology, a player’s deck of cards is called a library. The idea is that all of the creatures a player can summon and spells they can cast are contained in a “magical tome,” as Magic’s head designer Mark Rosewater calls it. Another method of winning the game is by making your opponent draw all of their cards, thus depleting their library and making them unable to draw any more magical knowledge from it. This concept is reflected in the design for the backs of cards, which is standard across each quarterly set. It loosely resembles a mottled calf binding with a central panel, a la the early 18th-century Cambridge style. The book form was further reinforced in the packaging of the earliest starter decks, whose boxes featured page edges and even a bookmark.

Beyond the intrinsic book-ness of the overarching game concept, books make frequent appearances in card art. Wizards of the Coast contracts numerous individual artists to illustrate Magic cards after the cards’ mechanics have been devised by the game designers. Broadly, if a book is featured as the main subject of a card, it implies that the spell or creature will have some effect on your or your opponent’s deck.

For example, here is a card called Rousing Read, from the Core 2021 set. This is an Enchantment that can be applied to a creature card -- Its effects benefit the person playing the card, and it also tells a story. First, when played, this enchantment requires the player to draw two cards (ie, turn pages in their library) and discard a card (ie, prioritize the information they wish to retain). Then, the creature to which this enchantment is applied gets a power boost and, importantly, flying. When a creature has the “flying” ability, that means it can’t be blocked by most other creatures. Finally, to make the narrative of the card more explicit, the so-called “flavor text” in italics reads “Great literature can transport the reader.”

A relatively new addition to the world of Magic the Gathering is the online version of the game, called Magic Arena, released in 2018. Arena allows you to face off with other players around the world, or to play against the computer. For mechanical purposes, the game remains the same; the card art -- front and back -- is also the same. All cards released in physical sets after 2018 have been simultaneously released in Arena, although there is no ability to transfer cards you own into the game or vice versa. The main difference in gameplay is the addition of sound effects, voicing, and animations, though these are generally reserved for particularly powerful cards.

In order to get a sense of how many cards across all Magic sets feature books in their art, I searched the Gatherer and Scryfall card databases using the following bibliographic key words:

book, tome, codex, library, librarian, archivist, archive, page, read, scroll, biblio, folio, grimoire

Out of around 22,000 cards, this turned up approximately 100 cards. But this does not quite paint the whole picture, as you can see with these cards. As an alternate sampling method, I selected six sets, and looked for books in each card in the set. For example, keyword searching only turned up one book card in the 1998 Urza’s Saga set, but in a visual review I found 19 cards that feature books. Some sets have no books: the H. R. Giger-esque New Phyrexia set, released in 2011 and taking more inspiration from science fiction than classic fantasy, lack any book cards. The 2021 Strixhaven set is particularly book-heavy, thanks to its setting at a magical university. This set has by far the most book representation of all those I looked at: 71 of 296 cards feature books in their art. However, Strixhaven doesn’t have a particular abundance of cards that affect libraries; many of these books are more setpieces than active elements of the cards.

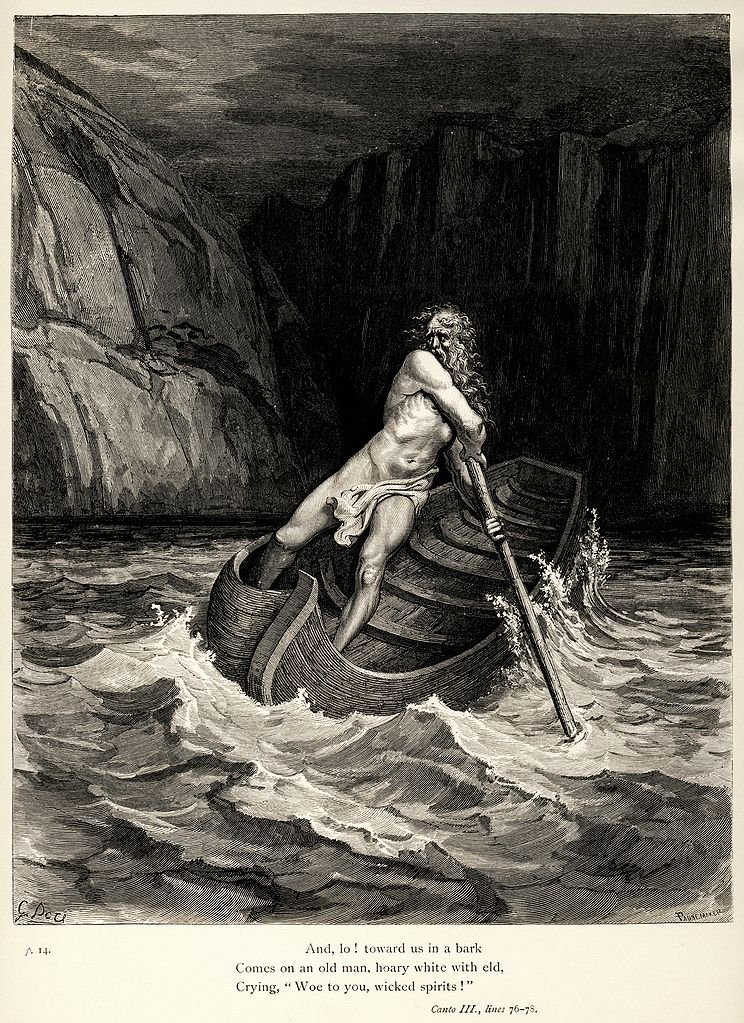

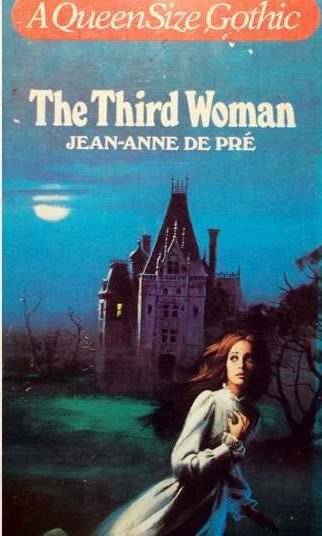

Bibliographic influence can also be seen in the aesthetics of cards that have nothing to do with books. The below land cards from the most recent set, Innistrad: Midnight Hunt, are quite clearly inspired by the wood engravings of Gustave Dore. This set has a gothic feel, and Dore’s style is an efficient visual shorthand to immerse the player in that sort of distinctly Victorian creepy vibe. But this set doesn’t just draw from classic gothic imagery: in the fantastically-named card Hostile Hostel, we see a direct reference to the “woman running from spooky house” composition, which adorned the covers of numerous gothic romance novels of the 1960s and 70s.

I have selected four specific cards as examples to explore through a material culture lens. Three of these cards are available in digital format; the first card appeared in a set that was released prior to Arena’s 2018 debut. I have included the one card that does not appear in Arena as a point of reference, as both the game mechanics and settings have become more complex over the years. I reached out to the artists for each of these cards and asked them about what resources they used as references.

First up we have Geth’s Grimoire from the 2004 Darksteel set. This card art was created by Heather Hudson, who has provided the art for 198 other cards. The most striking feature of this book is obviously the human face, which is clearly a reference to the idea of anthropodermic bibliopegy: the practice of binding a book in human skin. The chain is also featured prominently, an element that pops up in a great deal of fantasy art. The rather creepy design is reflected by the card’s effects and flavor text, which indicate that this Grimoire imprisons a spirit that only finds relief when the player opens it (ie, draws a card from their library). Hudson recalls that she used an “old Webster’s dictionary” as the model for Geth’s Grimoire, noting that “a big unabridged dictionary makes a pretty good tome.” Hudson was working on the art for this card in 2003, in a “time before the internet” for her; she found many of her references in the pages of National Geographic and around her own home. In terms of the general feel she goes for with her books, she says that any of the books she’s painted “would fit into [H. P. Lovecraft’s] Miskatonic University or [the Discworld] Unseen University” library.

As Hudson has been working on MTG art since the first sets in the early 90s, she was able to give a peek into how the art direction has developed over the years. She recalls that in the early days, artists had a huge amount of freedom, for good and for ill. More recently, she describes how “concept bibles became standard for each story arc… thick stacks of bound photocopies, mailed to the artists with their art orders.”

Next up we have Urza’s Tome, from the 2018 Dominaria set. The art for Urza’s Tome was created by Aaron Miller, who has illustrated 113 other Magic cards. There’s a lot going on here with both the form of the book and its setting. Beyond the metal furniture of the binding and the brightly gilt edges, the background is immediately recognizable as a library. Albeit a magical one -- we can see here a floating book restrained by a chain.

Miller’s main inspiration for the setting of this card was the reading room at the Art Institute of Chicago, though he notes he scouted other Chicago library locations. He also used a personal copy of the works of Shakespeare for a reference for the gilt edges, alongside “a host of images from the internet.” When asked if he could recall if any of the sources he used were provided by libraries -- a question I intended to explore his use of resources such as the Folger Library’s digitized bindings -- he responded by focusing on his use of digitized texts rather than material aspects represented in the digital objects. This may well be poor question wording on my part, but it also reveals a potential gap in the general public’s awareness of visual resources that they can find in a library’s digital collection. Miller also mentioned that Wizards of the Coast gave him a “World Book full of concept art and ideas that each set pulls direction from,” also noting that, in general, artists have “a lot of creative freedom within the box of supplies [they] are given.”

Now we come to Tome of the Guildpact, from the 2019 Ravnica Allegiance set. This card was illustrated by Randy Gallegos, who has illustrated 178 other cards for Magic the Gathering. Again, here we have some excellent metal furniture and a nice chain. But what led me to reach out to Gallegos about his inspirations for this card is the damaged spine, revealing the book’s gatherings. Gallegos notes that he used “a book we have here, a Spanish-language history of Ecuador that is an old family-owned book of [his] wife’s” that has a similar pattern of wear. And while he also used “a number of photos of old books, including ones that have chains and such” that he found via image searches, he expresses a desire for additional visual resources: “these old books are themselves fascinating as artifacts, even without the information they carry within.”

Gallegos was kind enough to include the whole pitch that he was given by Wizards of the Coast for Tome of the Guildpact, which is as follows:

Art Description: --

Setting: RAVNICA

Guild: None (but associated with all the guilds)

Color: Colorless artifact

Location: Unimportant

Action: Show us a large, ornate book bound in leather and metal. The book is shut, and might even be locked. We’re looking at its cover, which bears a symbol featuring all ten guild symbols, something like the one seen on [reference to style guide]. We’ve seen this seal a number of times now, so feel free to deviate from the design and/or make it relatively subtle—maybe embossed? (Do keep the guilds in the same order, please.)

Focus: The book

Mood: Within these pages is the soul of Ravnica.

I’ll focus on the physical description -- “large, ornate book bound in leather and metal,” and the mood -- “within these pages is the soul of Ravnica.” Gallegos blended these two concepts to create an image with the desired narrative weight, giving the book evidence of wear to communicate its importance through the implication of use. His inclusion of a hand for scale also acts as a conduit for a viewer to imagine touching the book themselves.

Saving my favorite card for last, we have Codie, Vociferous Codex from the 2021 Strixhaven set. Codie’s artist is Daniel Ljunggren, who has illustrated 175 other cards. This is another book with a face, but different from Geth’s Grimoire; in this case, this is the book’s own face, with features created through the skillful placement of metal furniture and ornamentation. Ljunggren notes that he started from the idea of a book with a polished stone in the center of its binding, which he used as a jumping-off point to make Codie have a single central eye. Codie’s metal eyebrow serves no codicologcal purpose beyond decoration, but Ljunggren says he imagines Codie’s nose-like clasp to be fully functional. Codie moves around with the assistance of a wrought iron book stand.

In addition to the artistic pitch for Codie, Wizards gave Ljunggren direction on the “tone/attitude” of the card. Codie was designed to be “A grumpy knowledgeable tome walking around questioning the students' presumed lack of skills.” Ljunggren was particularly focused on getting these character traits across, he recalls, “making it feel like a living being.”

Codie became the mascot for the Strixhaven set, appearing in animated commercials, where he speaks with a New York accent. He also appears as a dynamic pet asset on Arena. Pets don’t give the player any in-game advantages, and are more an effort to entice players into buying in-game currency to show off against their opponents. You can see that in his translation to an animated character and digital asset, Codie’s clasp nose has fused with his eye, rendering the mechanism unusable, but keeping with the aesthetic of Ljunggren’s design.

The Codie pet hangs out on the left side of a player’s screen, overseeing their actions. He has a couple of unique animations, such as this one for when a player wins a game…

And this one for when a player loses. The loss animation is particularly interesting to me -- it looks almost like one of his gatherings becomes loose when he falls off of his stand.

I asked Ljunggren specifically if he had any input on these other versions of Codie and their animations, and he reported that he did not. This is an interesting case of a material culture game of telephone. From an initial, dynamic physical book, to a set of static images on a website, to a static piece of art, and back to a dynamic animated object. It is interesting to observe how the idea of a book shifts and changes between formats, with each medium further distilling the idea of the codex form.

Some common themes emerged in these artists’ interviews -- namely, the use of Google image search and Pinterest to locate reference images. This is a more efficient use of time than combing individual libraries’ digital assets, especially if one is unfamiliar with using them in the first place. It also shows the slight disconnect between how rare book professionals understand and undertake digitization -- namely, creating a digital object that accurately reflects a physical one -- and how people outside the general milieu of rare books may conceptualize a digital book -- namely, primarily as a way to read text on a computer rather than on a page.

There are many more cards within Magic to be examined bibliographically, and with massive card databases like Gatherer and Scryfall, a lot of interesting dataset analysis could be done. It will be interesting to watch the expansion of Magic Arena, and how it continues to dynamically incorporate the ever-growing number of cards that feature books.

[With thanks to all the artists who responded to my emails!]