Myth Busting Metal Type

This is an edited transcription of an episode of my YouTube series, Bite Sized Book History. Check out the video version here!

So, everyone knows in 1450, Johann Gutenberg invented the printing press. Right? Well, that’s not quite right, on a couple of fronts. The screw press, as a mechanism, was present in the West starting in ancient times. Pliny the Elder actually wrote about it in his chronicles. It was used throughout the centuries for a variety of purposes, including as a wine press, and as a press for printing patterns on clothing. Gutenberg did alter the mechanism of the press somewhat to apply a more even pressure, but that’s about where his interaction with the press mechanism stopped.

Jikji, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Gutenberg’s true invention was moveable metal type. Right? Again, not quite. The Chinese were actually using moveable bronze type in the 12th century. Before that, they used moveable ceramic and wood type in the 11th century. This technology spread throughout Asia with the growth of the Mongol Empire.

The earliest surviving book printed with metal type is the Korean Jikji, printed in 1377; Jikji is the abbreviated title of a Korean work of Zen Buddhist teachings. Widespread use of metal type in Korea was stymied by government restrictions on its use, which was limited to official publications.

There’s no evidence to suggest whether or not Gutenberg knew of these Asian advances before he started his work, but he was certainly one of the first, if not the first, to use moveable metal type in the West. Gutenberg’s most important contribution to the technology of printing was the technique used to cast individual pieces of type. Trained as a goldsmith, he was familiar with a variety of metal casting techniques.

So, how do you cast an individual piece of type? The first step is to carve the letter backwards onto a small steel rod called a punch. The punch would then be punched into a softer metal, called a matrix. Though the punch is backwards, the matrix is the right way around. These would’ve been used as the base for a mold with which you could cast individual pieces of type over and over and over again. This was far more efficient than individually carving each piece of type, which could be thousands and thousands of letters and symbols to make a complete book.

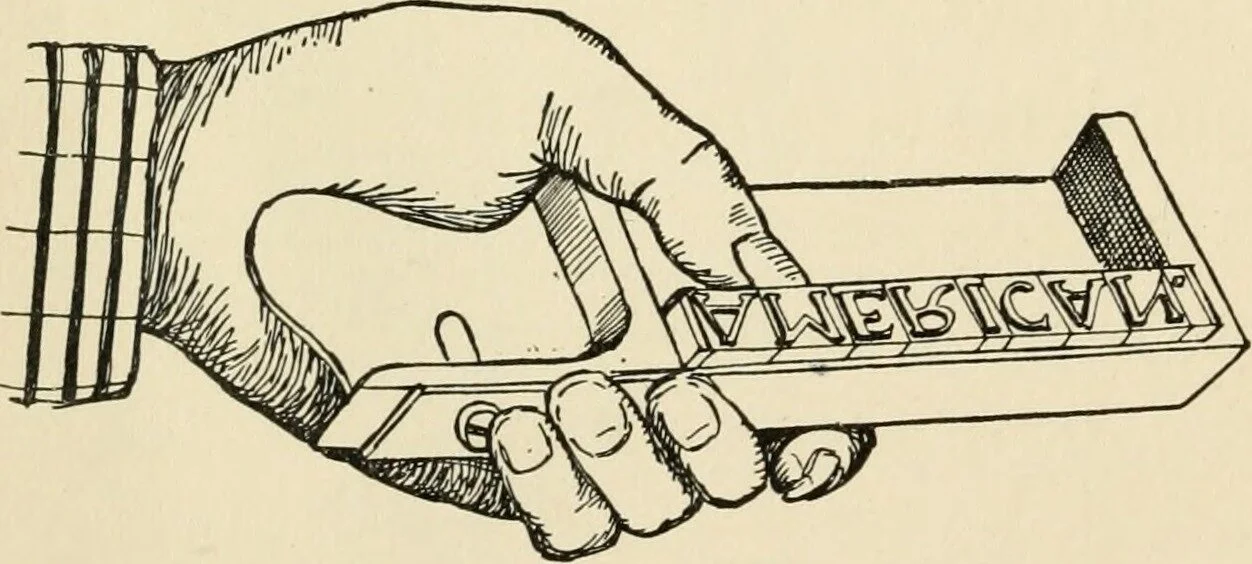

Now, once you have your pieces of type, it’s time to set your page… backwards, and letter by individual letter! This was a very time-consuming process, and very fine work. Pieces of type were sorted into little compartments within larger cases, with capital letters occupying the upper case — that is where the expression comes from! The letters would then be arranged onto a compositing stick, and eventually all put together to make a page.

This is an example of a page of set type. All of these little letters were individually set by hand, a process that had to be very exact: if you make a mistake, you have to stop the presses. Proper setting into the bed of a printing press involves a frame called a chase, and a variety of wooden wedges and sticks to make sure that it is absolutely secure and no type comes loose with repeated pressings.

As you may expect, typesetters weren’t always perfect. The expression “mind your Ps and Qs” actually comes from typesetting. And even the Gutenberg Bible had typos. But one historic example of a typo is a bit more… salacious than others. In 1631, the so-called “Wicked Bible” was printed, in which some unlucky typesetter left out the word “not” from a critical commandment, so it read, “Thou shalt commit adultery.”

Generally, metal type was for printing in a single color. Although it could be used to print in two or three colors, it was a time-consuming and very exacting process; each color had to be inked separately, and a page would have to be run through the press multiple times to pick up each color. This further required the page to be set in exactly the same position each time, so all the colors lined up in the finished product.

Later technological advances made it possible to cast whole lines of type at the same time. One of these technologies was the aptly named linotype. But the advent of linotype and, later, digital solutions did not kill moveable type. It is still used today by letterpress printers, including Star-Shaped Press in Chicago. They make incredible pieces of art using type not only as it was meant to be set — as words — but also to be combined into shapes, cityscapes, animals and more. They’re just one example of how people are putting their own modern spin on this classic art.

[Transcription by Alex Kyrios]

Sources and further reading:

Burke, Peter. “Three Print Revolutions.” Tibetan Printing: Comparison, Continuities, and Change, edited by Hildegard Diemberger et al., Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2016, pp. 13–20. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h246.6.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/155932#page/53/mode/1up

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OVvbWdXRMQs

https://www.wired.com/story/how-letterpress-printing-came-back-from-the-dead/

Eisenstein, Elizabeth. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

Garfield, Simon. Just My Type. London: Profile Books, 2011.

https://archive.org/details/cu31924031471562/page/n62/mode/1up