Who Gets to Be Bookish in Magic: The Gathering?

Art from Andúril, Flame of the West, by Irvin Rodriguez

Aragorn, the Uniter, art by Javier Charro

Anger over people of color in fantasy and science fiction settings is very predictable (see “The Little Mermaid” (2023), “Thor”’s Heimdall, “Star Wars”’ Finn), but The Lord of the Rings series and its associated stories seems to be a particular lightning rod for this kind of racist outrage. Just as Amazon was the recent target of accusations of “historical inaccuracy” and “not being true to Tolkien’s vision” over the casting for their “Rings of Power” series (2022), Wizards of the Coast is receiving pushback for their depiction of Aragorn as a Black man in a new Magic: The Gathering set based on The Lord of the Rings. As of writing this article, the card art for this set is still being released (update: we can see the whole set now!); we have glimpsed three of the main Hobbits, a band of orcs, and a bedraggled Gollum, but it is clear that, as in the books, Aragorn is the main focus of the battles and physical action.

Depicting Aragorn as Black is a bold – and calculated – move on the part of Wizards of the Coast (WotC), Magic’s parent company. Now in its 30th year of existence, Magic has long had a reputation (deserved or not) for being the realm of white, straight, cis dudes with a predilection for gatekeeping. I cannot speak to the demographic makeup of every local game store-hosted Friday Night Magic, but in the number I’ve gone to in the past five years, that type of player is certainly present. But so are plenty of women, people of color, gender nonconforming people, queer people, and people playing for fun. This increase in diversity has been cultivated by WotC, both by making it clear in their code of conduct that harassment and bullying of any sort are not welcome in game communities (though it could be argued this standard should be more enforced at events), as well as through the kinds of people they feature in their cards and stories.

The Lord of the Rings set doubles down on WotC’s stated commitment to diversity, hitting naysayers in another realm that has traditionally been white, straight, cis, and male: bookishness. Bookishness, by Jessica Pressman’s definition, is “about class and consumerism. It is about constructing and projecting identity through the possession and presentation of books.” Part of the reason a Black Aragorn is raising certain hackles is that it is perceived to threaten not only whiteness, but bookishness. Anything to do with The Lord of the Rings is inherently bookish; as the series originated in book form, interpretations of and conversations about the story at the very least must acknowledge Tolkien’s source material.

Ballantine Books paperbacks

As The Lord of the Rings gained cult status in the US in the late 60s and 70s with the publication of the Ballantine paperbacks, copies of the books were passed around friend groups until they were read to pieces. References to characters and events became a countercultural social marker (see: Led Zeppelin’s discography, the “Frodo Lives'' graffiti campaign, “Not all who wander are lost” bumper stickers), identifying people who were bookish enough to have found and read the series (or at least, wanted to be seen as such). With this sustained following came interest in adapting the books into other media, from animated films to games and eventually to the Peter Jackson blockbusters that truly made the series mainstream.

Each adaptation has had its critics; I will be perpetually disappointed that Tom Bombadil doesn’t appear in Jackson’s “Fellowship of the Ring.” In many cases – even in my example – these criticisms revolved around how “true” the adaptations were to the source material, taking the books as the sacred and immutable Originals. This is understandable: after all, the story as contained in the books is what initially led to its popularity. But even I admit that spending narrative time on the Tom Bombadil subplot in “Fellowship” would have made the already shockingly long (at the time) movie untenable. When adapting a book, certain changes must be made to suit the conventions of the media it is being adapted to, and that media’s target audience.

In many ways, this creates an opportunity for some fans to reassert their bookishness; the oft-heard remark “the book was better” implies that they read the book in the first place. The veracity of that statement is highly subjective, and ignores a key part of the capitalist media machine: this adaptation isn’t (just) for fans of the book, it’s ultimately to grow the story’s audience and to make someone more money. The same is true of the marketing and design of Magic as a game.

But to attribute diversity and Black Aragorn purely to capitalism also misses a lot of nuance, as well as the internal politics of WotC that go on behind closed doors. Within each decision like this are individual people fighting to get representation into the game. They may have to frame it capitalistically to get the people with the purse strings on board, but their persistence undeniably has a positive impact.

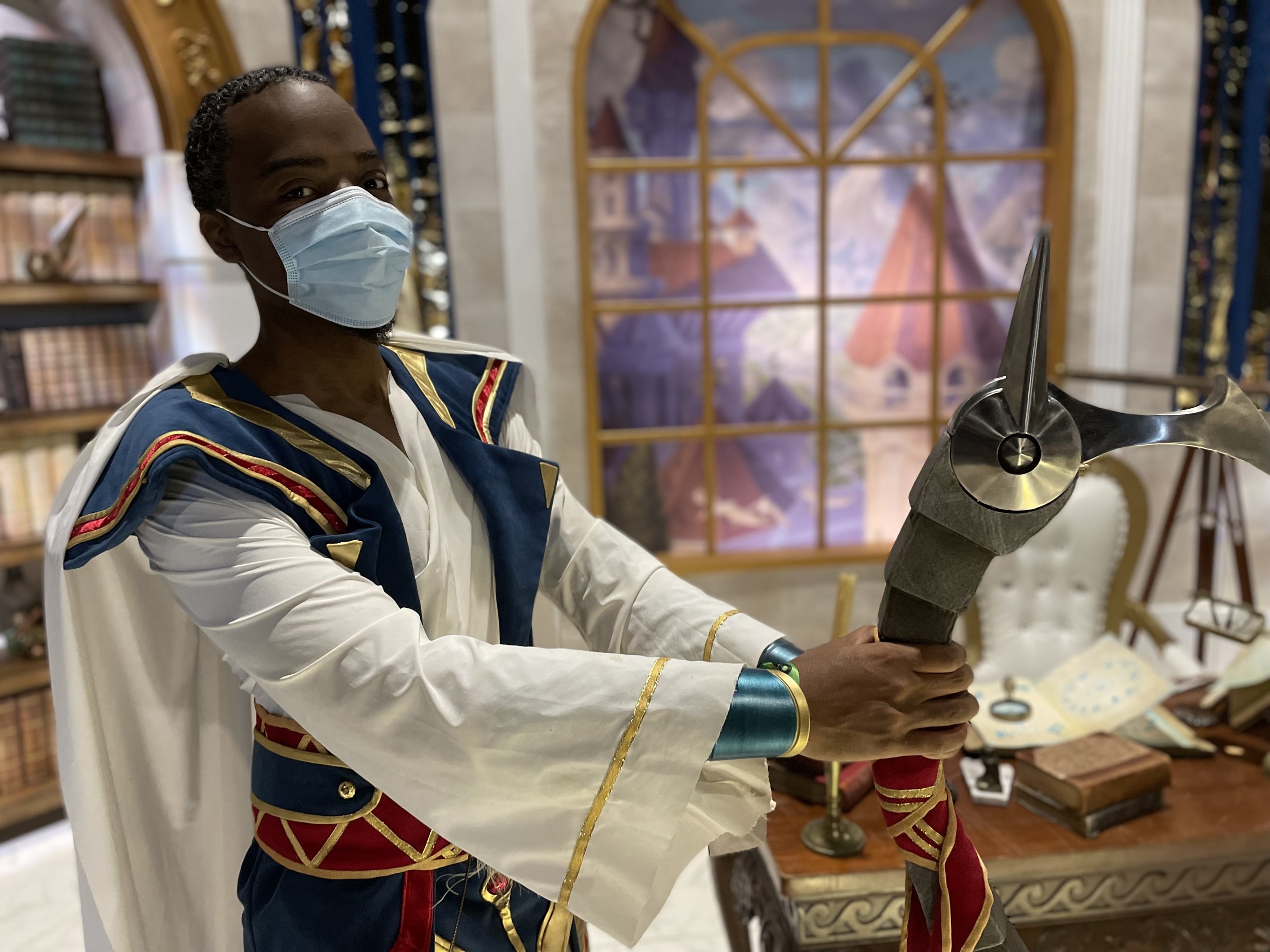

Powerful Black characters have been part of Magic from the very beginning, even before the game had a cast of regular main characters and storylines to return to. In recent sets, Black planeswalker Teferi has played a pivotal role in defeating an H. R. Giger-esque evil, and glorious Black knights, druids, queens, and gods have kept the multiverse safe. Indeed, specifically bookish Black characters have been key figures in sets particularly over the past five years, including Zimone the scholar, Alaundo the seer, and Teferi himself. Teferi especially has bookish overtones in his cards and how he’s promoted: at the kickoff event for Magic’s 30th anniversary in Las Vegas, a costumed Teferi actor was stationed in a library set, with books covering shelves and desks. But in the past 30 years, who really has been able to be bookish in Magic? With a pool of over over 22,000 unique cards (and more being released in around four sets per year), it is possible to compile trend statistics from Magic card databases such as Scryfall.

Graph I

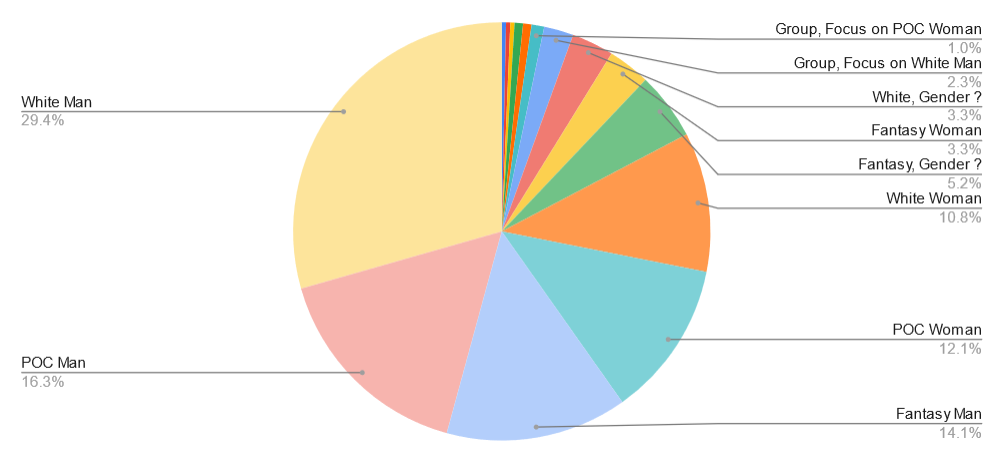

Obviously, not every Magic card contains a book, and not every card containing a book also contains a person. Out of 22,000 cards, I have identified 400 with books in them*; of those 400, a little over 77% – around 308 – also contain a sentient being (Graph I). The worlds of Magic are, of course, part of the fantasy genre, so these beings are not always human, or even humanoid – this octopodian sage isn’t letting a little water get in the way of their library research.

Graph II

Within the 307 cards with sentient beings, over the 30 years of Magic’s existence, white men are most frequently depicted using books or in bookish settings at 91 cards (Graph II). Men of color are the second most, with 50 cards. They are followed by men of fantasy races at 43 cards. (That these top three categories are men also speaks to issues of gender representation in Magic, which is a topic for a different article.) Women of color feature on 37 bookish cards, and white women on 33, with smaller proportions composed of women of fantasy races, mixed groups, and beings of indeterminate race and/or gender.

Graph III

Graph IV

The distribution changes when looking at sets from the past five years. For the sake of more relevant comparison, I’ve narrowed the categories to exclude fantasy races and groups, for a total of 210 cards over the history (Graph III) of the game and 102 since 2018 (Graph IV). Women of color are currently the most bookish demographic in Magic, followed by white men, men of color, and white women.

Art for Aragorn at Helm’s Deep scene box by Jason Rainville

Black Aragorn should be understood in the context of this recent worldbuilding – making a prominent character with bookish roots Black is absolutely consistent with these established conventions. The argument of the racists could thus be turned back on them: obviously they don’t care enough about the worlds of Magic to understand how this version of Aragorn accurately fits into the broader structure of the game. But, as we know, clapping back at racists is not always the most productive use of our time (though it can be satisfying). Instead, the Magic and The Lord of the Rings fandoms will speak in the way they have always spoken: with their wallets, sure, but also with grassroots hype and transformative fanworks. Depicting Aragorn as Black works to open doors to Tolkien – and bookishness – for audiences who have not previously been able to see themselves in the overwhelmingly white male source material.

——

* This was done by visually reviewing the entirety of each set as of June 7th 2023. It is possible that this number may be slightly higher based on human error, but there are no fewer than 400.